Mexborough & Swinton Times, October 28th, 1932

The Last Survivor

Wombwell’s Man’s Memories of the Oaks

A Fearful Calamity

Vivid Narrative by a Man of 86

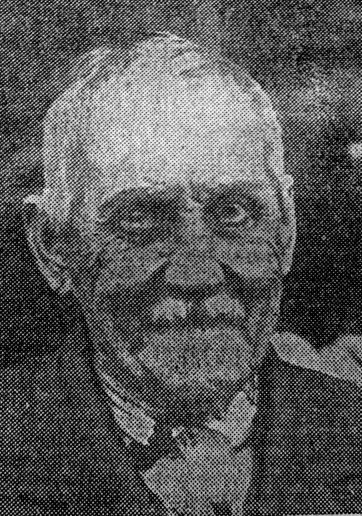

The village of Hemingfield has an old miner in whose mind there are stored recollections of the latest catastrophe in the history of the Yorkshire coal industry. He will be 86 next May, and believes he is the sole survivor of those who volunteered for rescue work , at the Oaks Explosion in 1866. The veteran is Mr. Mark Blackburn, 14, School Street, Hemingfield.

Mr. Blackburn, whose wife died twenty years ago, has five sons and three daughters, and one of the girls. Amelia (Mrs. Evans) keeps house for him. He has 24 grandchildren and numerous great-grandchildren.

A “Times” representative who called at the house found Mr. Blackburn communicative, though somewhat deaf, and otherwise physically fit and looking much younger than be is. He worked at Wombwell Main until he was 76 and has had his share of ups and downs, but has always enjoyed good health. He never had a doctor’s bill in his life.

The Oaks explosions occurred on Dec. 12th and 13th, 1866, and it is remarkable that a man who helped in rescue work at that date should now be living. Of the 340 men and boys who descended the shaft on Dec. 12, 1866 only 20 were rescued and only six survived. After the first explosion 198 persons forming rescue parties, descended the mine, and in a subsequent explosion 27 of these lost their lives, making a total death roll of 361. When operations were abandoned there were 396 bodies in the pit. A relief fund was started and the total subscriptions reached £48,747 3s. Queen Victoria contributed £200, and among other subscribers were: “A.Z.” £1000 and Earl Fitzwilliam £500. Chargeable to the fund were 68 men, 248 women, and 374 children, a total of 690 persons.

Mr. Blackburn recalls that when the Oaks Relief Fund was opened the miners at all the collieries in Yorkshire contributed a shilling a week each for two years. Twenty years ago, as one of the rescuers, he commenced to receive allowances from the fund, first at 5s. then 7/6, and now 10s. a week.

In the first place the pensioners had to queue for their money at the offices of Lancaster and Sons, Barnsley, but the line gradually dwindled as one by one the pensioners dropped off. The forlorn little band of crooked men with sticks greet each other no more. On account of the cost of travel Mr. Blackburn goes to Barnsley only once a month to draw his pension and looks in vain for his old pals. It is possible that the last of the old band that he spoke to, John Riley, of Ardsley, might still be in the land of the living, but he is not sure. For many years Mark and John used to write little epistles to each other, but John’s letters became few and far between, end eventually dropped off altogether. Therefore. Mr. Blackburn thinks he is the last survivor of the rescue party.

The Hemingfield Volunteers.

Mr. Blackburn related to the “Times” representative the circumstances under which he joined the rescuers. At the time of the explosion he was working at Wombwell Main, and on the morning following the catastrophe he rose early as usual to go to work. The proprietors of the Oaks Collier had been appealing for volunteers. Mark had got half-way to the pit when he met a number of friends, and together they talked the matter over. Their minds were quickly made up and they set off to walk to Ardsley, the little party consisting of Mark Blackburn (19), Wilfred Beaumont (17) his cousin of Elsecar, John West of Hemingfield, Barry Fenton of Elsecar, and Wm. Fisher (an oldish man) of Hemingfield. All are now dead but Mark. “I was a bigger chap then than I am now,” he said.

Reaching the ill-fated mine about 6 a.m., they found hundreds of people crowded round the colliery and a lot of men with drawn faces on the pit head. They were glad enough to have the offer of new help, and so the Hemingfield party were sent down the mine immediately. This was before the second explosion.

“We set off clown the travelling road,” said Mark, “and had not gone far before we came across dead men. They were lying about just as they been working, and you might have thought they were asleep. Some of them were stripped to the waist and they all had been caught by gas. Not one of them had been burned or otherwise injured. Others were holding each other by the hand, as though they had collapsed while groping their way to the pit bottom in the darkness. We proceeded about a mile from the pit bottom and altogether we saw about 24 bodies.”

A Minute off Death.

Mark said their little band was proceeding further into the workings to see if they could find any men whose lives had been spared, when they all felt a “puff’ of air. They stopped immediately, looked at each other with silent apprehension, and then decided that it was time to be going back! Reaching the pit bottom, they found others waiting to be taken up by the cage and among them was Mr. Smith, the manager of the Lundhill Colliery. The officials acted with traditional gallantry and Mr. Smith insisted Clint the workmen should go up first. The Hemingfield party had just reached the top when the earth shook with a terrific bang. A minute later and they would have been killed. This explosion practically wrecked the pit and sealed the doom of the men waiting in the pit bottom. Mr. Smith was among those who perished. Altogether the Hemingfield party were down the pit for three hours, working in an atmosphere that was charged with deadly fumes. When they returned to the pit-bottom they brought two of the bodies with them. The catastrophe shattered the nerves of all who came through it alive, and for several weeks. Mr. Blackburn was unable to work.

Mr Blackburn is probably the only person left who actually remembers the great Lundhill explosion of 1857 in which 189 perished.