South Yorkshire Times, July 21st 1933

Art Of Canary Breeding

Lesson From A Wombwell Master

A Delightful Hobby

Vanitas Vanitatum

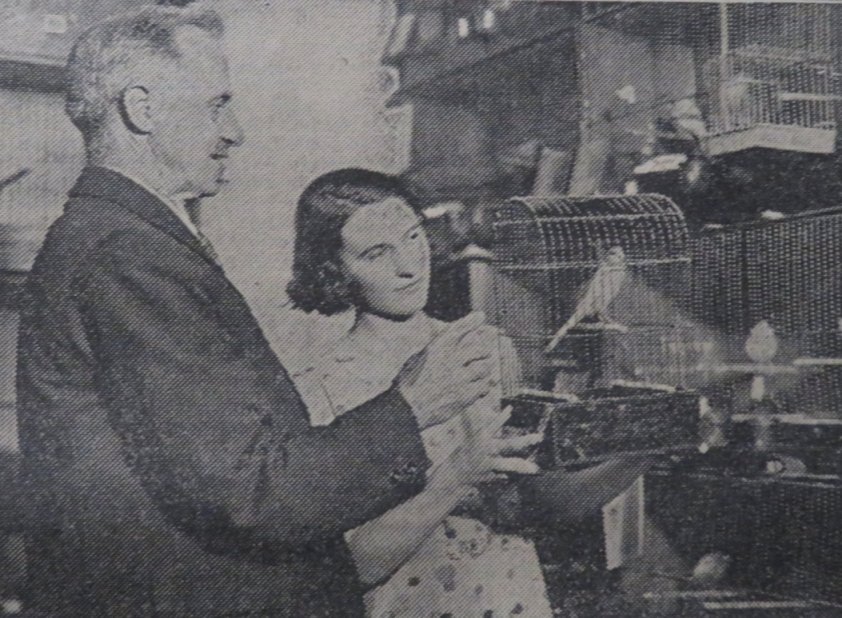

This is about canaries. In an upper room of a Wombwell house I have had the pleasure of inspecting some of the finer points of 110 prize specimens, many of them champions of three countries. and all bred by a Wombwell man who has a passionate love of cage birds. Mr. A. H. Waters, 138, Hough Lane. Wombwell, is an employee of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway. His name is a household word at all important shows throughout the United Kingdom.

Breed The Best

He first thought of breeding canaries over 30 years ago; now the hobby has become a part of his life. From the first he has concentrated on a good type. “One can breed champions quite as easily as ‘just good,'” he told me, “So why not” To start with, he bought four pedigree birds; and his present collection includes their descendants. All are of the prize class. He specialises on two breeds, Yorkshires, and Border Fancies: “The Yorkshires are the gentlemen’s fancy,” he said, “they are by far the hardier and better for show purposes. Border fancies make good foster parents—and the best songsters.

The Nest Pots

Mr. Waters first showed me his nest pots. These are about six inches wide and resemble shallow basins. They are made of clay porcelain and lined with felt. When the breeding season commences, they are placed into the cages along with a quantity of white deer hair. The canaries use the hair to line the nest pots for themselves, and in Mr. Waters’s words, “it makes them feel at home.” A canary lay three lots of eggs a year, and from three to five eggs at a time. As the eggs are laid, they are collected and filed in an indexed box until the bird has finished laying; this to ensure all the eggs hatching at once.

Learning The Ropes

This season has been a very good one for Mr. Waters. He has had some 50 youngsters, the last of them hatching out in June. Now they are beginning to “see the world” —the “cutest” little yellow fluffy creatures hopping about the cages with their proud parents. In many of the cages parent birds hop up and down on the perches and flap their wings in an endeavour to teach the youngsters the “ropes.” Father comes in for his share of the work in the rearing of the babies, for in most cases be helps to feed them. Mr. Waters told me that he has to keep a sharp eye on the hens. They seem to think the youngsters’ tail feathers make good nesting material and pull them out in no time. A canary derives much of its grace and poise from its lengthy tail, so that would never do. A youngster, he says, will look after itself after days, but until that time he has to be “nursed.”

The Menu

And what about a canary’s menu? This is no light factor in breeding. Their main diet consists of Spanish seed, but also includes rape, maw, hemp and niga seed. At the present time they are on a meal-and-egg diet, with a little seed, and on an average Mr. Waters’s birds use up from two to three fresh eggs a day. The greatest care has to be taken in preparing their meals, which they take three times a day. The eggs have to be boiled for about 20 minutes, allowed to go cold, and then put through a sieve and mixed with meal. Five cwts. of seed, two cwts. of biscuit meal, over £20 worth of colour feed, scores of eggs, and half a ton of sand constitute a year’s rations for Mr. Waters’s birds.

“Colour-Feeding.”

As I looked through the cages, I commented on some exquisitely marked birds of a distinctive golden orange colour. That, said Mr. Waters, was achieved through a process of “colour feeding.” When the birds are in moult they are kept on soft food, with which is mixed a tasteless pepper of dark maroon colour. One teaspoonful of this is mixed with half a pint of the biscuit-and-egg feed, and as the new feathers appear they are tinged with that delightful orange which makes a show bird so very attractive. Mr. Waters told me that an exhibitor does not stand a “ghost of a chance” at a show if his birds are not colour-fed. The process was “on the go” when he started breeding, and is greatly favoured among fanciers. The remarkable fact about this process, said Mr. Waters, was that only when birds are in moult will the pepper have any effect. It will not tint old feathers. With the aid of this feed and careful mating, Mr. Waters has produced some remarkable birds. “But the great art of canary breeding Is in the mating,” he told me. “There is a lot to learn about the game,” but that is one of the points he is emphatic upon. A young bird will commence moulting at the age of ten weeks. The older birds take anything up to ten weeks to complete the process. When Mr. Waters indicated some of the recent additions to his cages I noticed “fluffy hair” on their feathers. That, he explained, indicated the finer quality of their plumage, and was one of the chief tests for show purposes.

Training For Show

As the birds grow older, Mr. Waters singles out his own fancies for show purposes. “The last slump in industry hit breeders more than anyone can realise,” he told me, “and for that reason alone only the best are worth breeding.” Mr. Waters showed me one bird which has taken over 24 prizes up and down the country this year. He was a very “perky” little fellow as he hopped into Mr. Waters’s special show case. “He knows what he goes into a show cage for.” he told me. “Yon cannot frighten him by making a commotion.” The bird seemed well versed in show tactics, for as I looked round his cage he proudly posed, so that I could admire him from every angle. “I would not take for that little fellow,” said Mr. I Waters. Mr. Waters took other birds from their cages. Some seemed a little flustered. “Perhaps I am frightening them?” I suggested. “Oh, no,” said Mr. Waters, “that is the whole point of showing them. They must get used to strangers.” “How do you restrain their excitement?” I asked. He pointed to a number of hooks on the wall. “I take out a number of birds and hang them up there,” he said. “Then I cause a commotion round the cages. It they show a dislike to being on their own, I leave them there to get used to it. In any case a bird is no use to me it will not be trained. You see they know me perfectly.”

The Toilet

That was one secret; there are many others. The night before a show, canaries are care travis toilet rufus Toyota training good feeling and yeah fully washed with either Lux or Pears soap and warm water. When quite clean they are taken out and dried in silk. When dry, a canary is carefully sprayed to help him to arrange his feathers. Then—vanity of vanities! —he is placed in front of a mirror. There is nothing a show canary enjoys better than to see himself in a glass! And what airs he puts on! “If I place a looking glass in the bars of a show case,” said Mr. Waters, “the bird will instantly draw himself up, just to have a look. ‘That is how to get a bird in good mood for a show. Let it believe it is beautiful; it will become so. You should see them throw out their chests.” So even canaries are conceited! Mr. Waters told me he had certain birds be could send to any show without any fear of their being “placed.” That is what I mean by only having the best,” he said. “I never fondle them, but always give them personal care. That is the only road to success. Too many cooks in canary breeding spoil the broth.” Mr. Waters knows the pedigrees of his birds off by heart. He gives them no pet names, but would back some of them against any in the world. In the course of a long career Mr. Waters has won thousands of prizes. He showed me a box filled with exhibition cards from shows all parts of the British Isles. “Scotland,” he said, “is the only place where they make a charge for the prize-card, Sixpence is deducted from your prize-money. On the walls of the bird rooms are diplomas from Crystal Palace and Alexandra Palace shows, London, Bradford, Manchester and Sheffield.

Trophies

But his best collection of trophies is to be found in the drawing room. Mr. Waters has six silver cups which he has won outright, silver plate, fruit stands, and a silver tea urn. They include a cup presented by the Sheffield Ornithological Society in 1925, two cups won in Sheffield Cage Bird Society competitions, and a cup awarded by Mr. Fred Kelley, of Sheffield, which he won five years in succession. The tea urn was won in a Bradford Canary Club competition in 1909-10. Bronzes, a clock, china ware, and trinkets innumerable are among his trophies. There is not room in the house to display them. Mr. Waters is a member of the Yorkshire Union of Canary Breeders and also of the Yorkshire Canary Club. The club give their patronage to shows, and Mr. Waters has gained many of his awards in support of his societies. He has twice won a trophy offered ‘ for competition by the London, Midland, and Scottish Railway Company at Derby, and holds replicas. “That,” said Mr. Waters, “is what l am preparing for next. The show is to be held in Derby in September, and I hope again to carry off the trophy with that little fellow I showed you upstairs.” The enthusiasm of Mr. Waters is reflected in the success of the Wombwell Cage Bird Society. He is the “father” of that organisation and never grudges the practical hints on breeding and conditioning that he is able to impart to young fanciers. Known throughout the country as a “canary man” and an efficient judge of the birds, he commands respect by his quiet modesty, As I left, Mr. Waters was preparing the egg and meal feed for his birds. “They always get their meal before I think about mine,’ he said. As I left, sunshine came through the attic 1 windows and fell in slanting bars acro ss the limewashed walls. Reacting to it, the birds struck up in joyful oratorio. For a moment I realised some measure of the delight which Mr. Waters finds in his hobby.